Deconstructing Deconstructivism

Love of Ugliness for its Own Sake?

A Libido for the Ugly?

In this month’s post I explore an architectural movement that calls itself Deconstructivism. It is yet one more instance of the strange shapes that ‘Progress’ has taken on in the modern Western world. Buildings in this style seem like they have been constructed to appear as if there must have been a gas explosion inside or a bomb has been dropped on them. Deconstructivism can perhaps be best understood as the architectural equivalent of the current fad for deconstructing gender….. such that, whereas we once had an edifice called Men and an edifice called Women, now - in the parallel universe of gender diversity - we have man bits and woman bits strewn all over the place. This architectural movement has - over the last three decades, - dotted around the world some truly weird-looking buildings - including office blocks, museums, art galleries, stadiums and more. The ones illustrated in this essay were chosen using Creative Commons licenses but a quick Google Images search would reveal large numbers of much more bizarre examples. [Trigger Warning! (only kidding) If you are an admirer of these type of buildings (and/or abstract or conceptual art) you might want to give the rest of this month’s post a miss because – although I try to be fair – my own take in this essay doesn’t get any less unflattering.]

In 1926, the renowned American social critic H.L. Menchen wrote a famously acerbic essay The Libido for the Ugly in which he wonders if there “is something that the psychologists have so far neglected: the love of ugliness for its own sake”. I’ve always loved beautiful buildings. I wanted to be an architect right from when I was a small boy and I have spent a large part of my life – both as an employee and on my own account – in the business of building construction and conservation. But I really struggle to fathom how any of the buildings illustrated in this post could ever have seemed like a good idea. Not to the developer who commissioned them and not to the architect who designed them. And yet there they are.

We are talking about an architectural style that dates from the 1980s but has ideological roots that go back much further. The basic idea is this: let’s take something that you ordinary people ‘out there’ used to think of as ordered, graceful and beautiful and then let’s ‘deconstruct’ it. Trash it in other words. Shock you; ‘challenge’ you; disorientate you. “If you don’t get why we are doing this” they say “it must be because you are unsophisticated. It must be because you don’t get……………. The Future”.

Judged by the billions of dollars than developers and clients have poured into these buildings around the world and designed by much-feted ‘starchitects’, it is a very successful style. How can this be so? The answer, in truth, is hugely complicated – touching on political philosophy, technological change, mass media, social psychology, megalomania, alienation, narcissism, boredom even...all manner of things. But complicated is like a great overcast sky when all you really want is a little parting of the clouds and a bit of blue sky shining through. So in this post I’m going to have a go at a bit of that blue sky.

First of all: ask yourself this question: how many people if shown – say - Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring would think it a great work of art even if they didn’t know it was famous and valuable? And now ask yourself (hypothetically of course) how many would think that about Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d'Avignon if they’d somehow never seen – or even heard of - Cubism or any other type of abstract painting? And now ask yourself if you would know that Mondrian’s Composition with Red Blue and Yellow - is a great work of art if no one had ever told you so?

It is not my intention here to rain on the parade of anyone’s love of abstract, non representational art (although I guess, intended or not, that is what I am doing). My intention is to show that abstract art is essentially an educated aesthetic taste whereas representational art has a much more direct intuitive, visceral appeal to the great majority of people. And this distinction is very relevant to understanding what is driving the current vogue for Deconstructivism - a parade that I do indeed want to rain on.

“If you don’t get why we are doing this” they say “it must be because you are unsophisticated. It must be because you don’t get.. The Future.

Art for Art’s Sake. Architecture for Ego Sake

To understand how these buildings came to seem like a good idea, you have to look beyond the narrow frame of reference of architectural style and interrogate some aspects of social psychology that have grown up in the modern age - ones which we in the early 21st century now tend to take for granted. The master builders who built Europe’s Gothic masterpieces were not geniuses; they were just skilled (hugely skilled) craftsmen. Our genius notions like ‘original’ and ‘revolutionary’ would have meant nothing to them. In other words, they saw themselves as a humble part of something much bigger than themselves; it wasn’t all about their egotistical selves. Painters like Vermeer did become celebrities of a sort (either in their own lifetime or posthumously) but they were still pursuing something that was conceived of mostly as a highly skilful craft. They didn’t - beyond a very limited extent - intellectualise their creativity. Deconstructivism is the polar opposite of this; it starts with a theory – “let’s pull apart ingrained assumptions about how a building should be” (vertical walls, flat floors etc). In this way it is ‘intellectual’ - and arrogant.

The following quote (1934) by English architect Reginald Blomfield, gets - in my view - right to the essence of all this “..literature and the written word established a disastrous domination in arts not their own and all sorts of strange ideals were introduced and pursued with an enthusiasm which constantly missed the mark, because most of its aims were irrelevant to the art of architecture”. He was attempting to account for the rise of the pseudo-totalitarian Modernist Movement amongst the architectural cognoscenti and also to the various avant-garde fads then sweeping the art world.

What he was getting at was this: very few people can look at a Greek temple or a Gothic cathedral and not think it beautiful, graceful, elegant. These buildings have a near universal visceral, visual aesthetic appeal. You don’t need any words or arguments to prove that to them. Most people’s visceral reaction to concrete tower blocks on the other hand is aesthetically negative. They need a lot of sophistry and argumentation to persuade them of the putative benefits – rational construction, economic land use, integration with needs of the motor car etc.

Let’s be Original; let’s be Revolutionary.

There is of course nothing wrong with innovation per se; it is the knee jerk compulsion to innovate, or ‘reinterpret’ - as a kind of moral imperative, that is the malign 20th century aesthetic legacy. One thing that has always struck me as particularly absurd about the avant-garde art world – all the way from the early 20th century Modernists to the current crop of Damien Hirst-type Conceptual Artists, is how - for all their no-holds-barred iconoclasm - they still take it for granted that there will always be a thing called an art gallery and an exhibition for them to play their self-consciously revolutionary games in. Why cling to this particular comfort blanket? If there is to be a root and branch re-imagining of the meaning of creativity, why not ditch the art galleries? Why not ditch the very concept of “art” for that matter?

And what to make of the idiot cognoscenti that have elevated a fad fashion brand like Damien Hirst to the status of artistic genius? That rag tag of pretentious collectors, useful-idiot journalists and incontinent money baggers; plus, sadly, those easily biddable types who will trot along to any old Tate Modern knick-knack gallery theme park as long as it is billed as a tourist attraction. The real ‘genius’ of today’s conceptual artists has been their instinct for self promotion. Through the agency of their academia and media acolytes, they have so completely rigged the artistic terms of reference that any criticism of them, however intellectually compelling, is rendered axiomatically philistine, small-minded and out of touch. End of rant.... let’s return again to my main subject: architecture.

“the written word established a disastrous domination in arts not their own and all sorts of strange ideals were introduced… which… were irrelevant to the art of architecture”

Goethe - the great German man-of-letters - famously wrote that architecture is frozen music. It is a compelling metaphor but if architecture really was music then we would all be able to choose to inhabit an urban environment composed entirely of buildings of beautiful, picturesque or sublime quality. With all other art forms, you can seek out what is good and opt out of the rest.... but escaping bad architecture is much more difficult. You may even, if you are unlucky, have to live in it

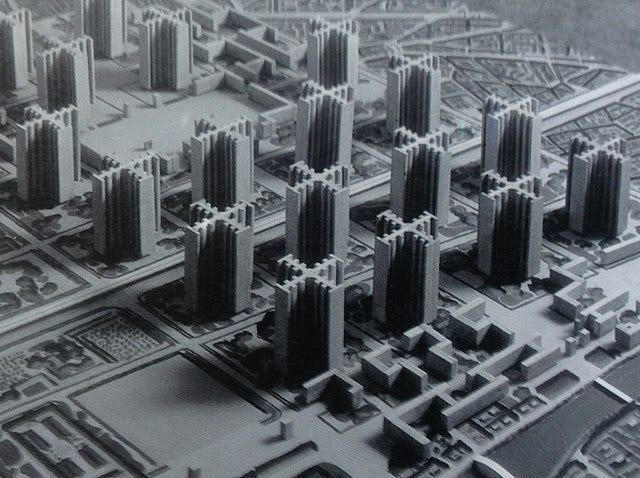

There has been more than one attempt in the last hundred years or so to effect a wholesale re-invention of architecture. The first – now notorious one - was Modernism most associated with the now discredited Le Corbusier. (C.E. Jeanneret Gris’s renaming himself in this way was perhaps telling – indicative of a sort of Bono-esque self-importance. But at least Bono had some good tunes whereas Charles Edouard’s utopian architectural ‘muse’ was entirely joyless and grim). Had he got his way, a large part of the centre of Paris would have been demolished in the 1930s because it did not accord with his ‘vision of the future’. Mercifully that didn’t happen but in the post war era from about 1950-1980 his architectural acolytes did bring into being his vision of the future across much of Europe and parts of America. This vision was in the shape of those ‘concrete jungle’ tower block complexes that town planners have spent the last thirty years demolishing (having previously been on the band waggon that brought them into being). For a deeper delve into this, Making Dystopia by James Stevens Curl is a great read which I reviewed here in 2018.

Almost everyone now understands that the Le Corbusian legacy was entirely malign, even if they have never heard of the man himself. Everyone that is, except in the ivory towers of architectural academe; its luminary authors of revered set texts and in the more high brow professional journals. I had first-hand experience of this at architecture school in the 1980’s. In my school, the status of ‘Corb’ (as we were encouraged to affectionately call him) as your ultimate architectural hero was, quite simply, a given and dissenting from this position was risky. Such is the power of group-think to which universities are sadly so very prone.

Two cancerous aspects of the faux-radical Modernist mindset have survived in our schools of architecture. One of them is the idea that an architect aspiring to greatness must also aspire to novelty. To insist that every kind of building aesthetic ‘must’ be ‘modernised’ to suit some perceived advancing zeitgeist is almost as absurd as proposing that any of life’s simple pleasures ‘must’ be modernised; that maybe even sexuality be modernised. (Come to think of it now, aren’t there some in our society advocating something just along those lines too?)

The other is the idea that building design has sociological, psychological and macro-economic dimensions which the architect – simply by virtue of his being an architect – is competent to judge. Words again! Pseudo-intellectual verbosity again....as so presciently warned of in Reginal Blomfield’s quote above. What really matters to your average architecture student is drawing. They are emphatically not deep-thinking psychologists, not economists and not sociologists and never will be because, for the most part, they are not deeply even interested in these disciplines. Which is fine and just as it should be until the bogus idea is implanted that their drawings represent some kind of implicit vision for mankind.

Two cancerous aspects of the faux-radical Modernist mindset have survived in our schools of architecture. One of them is the idea that an architect aspiring to greatness ‘must’ also aspire to novelty

If architects are in need of a statement of their mission they need look no further than Vitruvius’s ancient and eloquent aphorism - Firmness, Commodity and Delight – which still stands as a sufficient theoretical basis for any architectural project. But a required part of any architectural design is a lengthy verbal rationale – often post hoc and half-baked - of how the design is expressive of such imponderables as the psychological ‘needs’ and ‘aspirations’ of the users and the wider ‘community’ which the building is to serve. For a deeper delve into this, I would strongly recommend David Watkin’s seminal book Morality and Architecture about the emergence (from the late 19th century onwards) of verbose and alien notions about Honesty, Morality and Truth into the essentially artistic discipline of architecture.

I wish I could recall some of the glib rationales from my own student days where students regurgitated the bogus language of their tutors - in which buildings might be said to be ‘fun’, ‘thought provoking’, ‘democratic’, ‘inclusive’ and other such nonsense. Thought provoking Fun – there, in essence, you have the vacuous underpinnings of Deconstructivism.

It is been said that art is an expression of worldview. If one believes in beauty and purpose, divine or otherwise, one is likely to pursue that in his art. If one believes that the world is random and without meaning, her art will follow.

In either case, it seems telling that by deconstructing something beautiful, a building or a human, the deconstrctionist finds something ugly. Why? Perhaps it comes from within the artist.

So, if I understand this correctly, you don't like deconstructivism. As for the other pieces you cite, such as Mondrian’s Composition with Red Blue and Yellow, I see no reason to call it art except for a lesson was taught in a history of art class in college. Mondrian did it and that makes him an artist. Briefly, here is the lesson as presented in the form of a short film shown in a basement classroom: A man, I'll call him Bob, lived in a house on a lake shore with a dock that started some distance back from the water and extended out, meaning he could stand on the dock and look down at his beach. In the film, Bob got a sheet of plywood and put it on the shore. He then took random cans of paint, presumably left over from house renovations, and from the dock poured and splattered the paints in completely random fashion on the plywood. Once it was dry, he cut it up into smaller rectangles and framed it to be sold as art. Here it comes. The question was posed thusly; if anyone could do it, was Bob an artist? The professor said the answer was yes -- not because of the final product, but because he did it and that made him an artist when others either never thought of it or did but never did it. I have the ability to draw straight lines and fill in spaces using different colors, but I don't do it. On that basis, Mondrian is an artist and I am not. If being an artist is, instead, determined by the output, then who's to say? It is entirely subjective and if you get the "right" people to endorse you, you're an artist. Alternatively, you are an artist for being creative just, possibly, an unknown one even if just as talented as the famous ones.

Where does all this go? I think for a walk. It's a nice afternoon.