Once Upon a Time in the West

Our Civilisation Needs to Tell Itself a New Story

I keep reasonably abreast of what used to get called political current affairs via a daily read of articles and essays but I never seem able to get past the first chapter of any book on political theory or philosophy. For my interest to be sustained at book-length, it has to be fiction…basically novels. So my curiosity was aroused recently when I came across an article about a book by philosopher Richard Rorty published in 1989. The article’s author Michael Rainsborough characterises Rorty’s thesis thus:

“literature, not academic treatises, affords a truer insight into an understanding of the human condition. While professors are busy strangling everything with jargon and footnotes, novels and poems are out there doing the real work: showing us what it actually feels like to be alive.....Literature is a better moral compass because it throws us into the vivid chaos of individual lives, instead of forcing human experience into some procrustean theoretical framework. Sometimes a single sentence from Orwell, or Solzhenitsyn, or Camus tells us more about integrity, honour, cruelty and hope than a thousand pages of scholarly ‘analysis’ ever could.

Intrigued by this, I sought out Rorty’s book. True to form, I only actually managed a quick skim read of its 200 pages but his thesis resonated with me nevertheless. It is a theme I have occasionally touched upon in my own writing down the years.

So where am I going with this? The number of Westerners who - fearing their civilisation is in an existential crisis – are looking for radical political solutions now probably runs into the tens if not hundreds of millions. This is where Rorty’s insight comes in. Perspective on our current moral, philosophical and political discontents can, in his view (and mine too) be found only to a limited extent in political discourse – whether journalism or book-length. To get the full measure of that existential crisis, a wider-angle lens is needed.

How We Form Our Idea of Reality

There has been a good deal written in academic psychology about the importance of stories to the human psyche....how they help us humans make sense of our lives. In a nutshell, what has been found is that – contrary to the Enlightenment Age of Reason paradigm that people’s idea of reality is constructed from tools of logic and analysis – most people in fact, piece together their big picture of reality in large measure from narratives. They construct much of it from stories they have heard or read or made up in their own heads.

This is a subject too big to do more than touch on here but this snippet from a psychology thesis The Narrative Construction of Reality by psychologist Jerome Bruner gives a sense of the kind of argument being made:

“Surely since the Enlightenment, if not before, the study of mind has centered principally on how man achieves a "true" knowledge of the world…. Empiricists have concentrated on the mind's interplay with an external world of nature, hoping to find the key in the association of sensations and ideas, while rationalists have looked inward to the powers of mind itself for the principles of right reason. The objective, in either case, has been to discover how we achieve "reality," that is to say, how we get a reliable fix on the world..... [but]....while we have learned a great deal indeed about how we come eventually to construct and "explain" a world of nature in terms of causes, probabilities, space-time manifolds, and so on, we know altogether too little about how we go about constructing and representing the rich and messy domain of human interaction......As I have argued extensively, we organize our experience and our memory of human happenings mainly in the form of narrative-stories, excuses, myths, reasons for doing and not doing, and so on.....”

On a personal note, I first got some sense of all this as a young man by reading the works of the psychiatrist Eric Berne. He is most famous for his book Games People Play.....games like ‘Let’s You and Him Fight’ and ‘See What You Made Me Do’. But I was also struck by his idea that we construct for ourselves little subconscious life scripts to help guide us on how to go about our lives.

My theme in this essay is to look at how our rapidly evolving technologies of instant and constant social communication, may be crowding out our engagement with the kind of stories that span past, present and future. But first, let’s backtrack briefly to the more familiar territory of...

.....Politics as a Means of Setting the World to Rights

My Slouching Towards Bethlehem target audience has always been people looking less for current affairs commentary and more for undercurrents shaping it. The zeitgeist in other words. Having observed right-leaning Substack politics newsletters for over two years now, I am conscious that mine is a relatively small niche. The dominant market is for commentary (and venting) on the current here-and-now of Progressivism’s social and political folly.

Is mine just the perspective of a man in the autumn of life you might ask? I am conscious that someone younger - with much of their life still ahead - might feel a greater sense of urgency. They see the Progressive liberal paradigm as having disappeared up its metaphorical backside; they see a culture that has lost its moral compass…..and they want to know what can be DONE ABOUT IT. In those terms the Trump administration currently must seem to them to be just what the doctor ordered (but see below).

So is there any practical benefit to what I have just called a wider-angle lens? I believe so. Our age of mass communication wizardry has created an environment of information/disinformation overload which can make it difficult to see the wood for the trees. This Substack has, in a small way, been trying to thread a coherent narrative on how our Western Liberalism came to be the way it is. Unlike newsletter sites, I conceive of my essays (both here and as a contributor to various right-leaning magazines) as part of a whole. [if only one of my valued readers with connections in book publishing, knew of one who sees a market for a collection of essays by an elderly white male conservative; I’d be all ears!……… Only kidding.]

It is true that some kind of right-wing course-correction is happening - at least in America. The Trump administration seems to be miraculously up-ending a decades-long Progressive ‘consensus’ in a way that no one would have predicted twelve months ago. To those of us sick to the back teeth of the Long Twentieth Century’s great intelligentsia/middle class moral-posturing, this counter-reformation does feel like a breath of fresh air whatever other reservations one might have about it.

It seems, for instance, to be marshalling a degree of long-overdue common sense push-back against things like white-self-hatred-by-proxy-syndrome and chattering class hang-ups about normal sexuality between men and women. But as I wrote here recently, I am not convinced that the trajectory of Western Liberalism is really being that radically altered. This is because of my belief that evolving technology is a bigger driver of civilisational change than politics.

There is a growing, if inchoate, sense that the goal of an end to the bogus quasi-religion of Progressivism - that has sucked up almost all the energy on the Right - is not the whole story. One manifestation of this is how many well-known rightist intellectuals have, in recent times, been re-exploring Christian faith. And words like re-enchantment have started to enter the language of intellectual discourse. Both of these are signals of a sense that something else has gone awry with Western liberalism.

Which brings us back to my theme in this essay: how the digital age is changing our civilisation’s story, whatever kind of politics may currently be in the ascendant.

The Medium is the Mentality

Let’s now zoom out from political discourse to Marshall McCluhan’s famous insight that the medium of a given stage of mass communication technology is ultimately a more powerful influence on the way we perceive the world than any specific message content within that mode of communication.

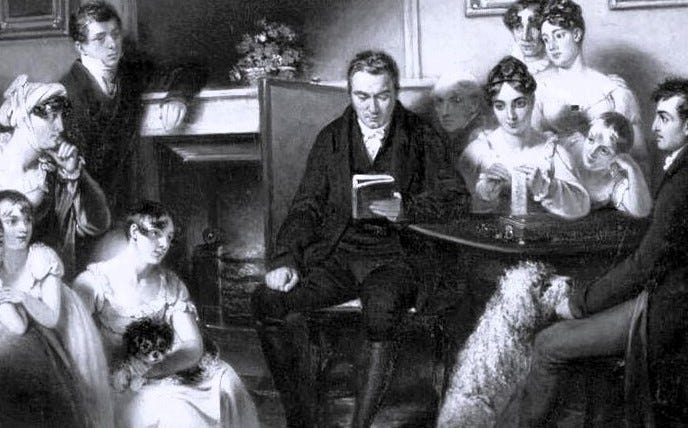

In our sepia-tinged picture of life before the dawn of mass-media, people used to gather round the proverbial fireside and tell each other stories. These were generally stories of a collective past...real or imagined. Folk tales, salutary tales and nursery rhymes with implicit guidance on how to be and how not to be. A story book of mythic heroic or dastardly deeds ranging across time and from the local to the cosmic. Even if this is a romanticised picture of a by-the-fireside past, it is a warming picture. Fast forward to our civilisation’s 21st c. and we seem increasingly to live a Twittified, Instagramed, TikToked, MSMed (and Substacked) PERMANENT NOW. Leaving less and less head-space for quiet reflection.

Before the age of mass media, most people inhabited a mental universe in which the daily fare of factual ‘news’ was localised and of a comprehensible scale. ‘News’ about the world beyond one’s immediate, intimate environment was scarce leaving plenty of head-space for other ways of viewing reality. So has the digital age diminished our capacity for those longer perspectives, thereby narrowing our mental horizons and impoverishing us?

Another brief digression:

A Partial Defence of Big Tech

It has become a near-universal journalistic stance to slag off Big Tech. I do not incline to join in with this hate-fest, even though I do believe it has had serious harmful consequences on the permanent things that we conservatives cherish.

Fundamental to being what I like to call a grown-up is understanding that to every upside there will always be a downside. So there will of course have been downsides to the awesome inventiveness in the field of communications technology over the past three decades or so. [As an aside: perhaps the simplest way to pin down the essence of Progressivism is that it is a juvenile mentality of upsides with no downsides.....a permanent have-your-cake-and-eat-it arrested adulthood]

My view of the overall cost/benefit ledger of Big Tech’s influence on our lives is a nuanced one. It stands accused of being monopolistic and addictive. True, but that is only half the story....the negative half. What gets left out of account is the enormous amount of intellectual freebies that the internet has afforded those with the wit to take the best of it and eschew the worst. To take things like Streetview and Google Earth entirely for granted and to tut-tut about things like Wikipedia for being...What - less than perfect? Whatever failings can be levelled at it, the invention of the search engine has been an absolute marvel....at least for anyone who manages to maintain a balance between intellectual curiosity and scepticism.

Apart from anything else, it is important to distinguish that digital age harms are of a fundamentally different kind to those brought down on us by The Long Twentieth century’s intelligentsia-driven ‘Social Justice’ posturing. Harms brought about by the digital revolution did not arise from narcissism and cant; they were just downsides of what clever men have always done.....invent things.

After this brief, partial defence of Big Tech, let us now return to the importance of narratives to our sense of reality.

The ‘Imaginative Conservatism’ of Russell Kirk

Rorty’s ideas on the importance of the literary imagination echo the insights of an earlier American philosopher; someone often seen as the father of modern conservatism - Russell Kirk. To give a snapshot of Kirk’s philosophical thought, I’ll quote briefly from this essay on him:

In The Conservative Mind (1953) “Russell Kirk.... sought to orient conservatism not toward temporary success in day-to-day political controversy but rather around what he called the ‘Permanent Things’ that constitute the ‘unbought grace of life’..... a conservative movement that is poetic rather than political..... More than written constitutions or abstract political theories, literature can express the true essence of a people and the fundamental roots of social order that we must strive to conserve..... [It is the literary] ‘keepers of the Word’.... more than the statesman,’ Kirk went on to argue, [who] ‘remind us of what Burke calls “the great primeval contract of eternal society, linking the lower with the higher natures, connecting the visible and invisible world”...... None of the factions competing for power in Washington possesses the poetry of the soul that is the conclusion of The Conservative Mind.”

In Conclusion

In this essay I have mused on the idea that a downside of the digital age is its cluttering up of our heads with constant NOW and thereby crowding out narratives that might give us a richer cognitive tapestry. That is a big indictment of the way we live now but I can see no realistic democratic political solution to it. It does not follow that I see the West’s future as necessarily a tragedy in the more commonly used sense of the word. I have no clear view what a post-Enlightenment future holds but suspect that its conceptions of liberty, freedom, democracy and the pursuit of happiness will depart - perhaps quite radically - from those still clung to by its current liberal establishment.

Some while ago, I had a daydream. In my dream, Western Liberalism’s great rise and fall had become one of many great tales shared around among the immortals in celestial eternity. Heaven has always been a conception rather sketchy on the details of what immortality would be like but I imagine it as somewhere in need of big engrossing stories to while away the ocean of time up there. Tales commensurate with Paradise Lost; Milton’s epic poem of the fall and redemption of mankind.

So what kind of a story would ours be? A kind of Greek tragedy is how I imagined it. One in which the protagonist’s tragic end was ever-present in its very beginning. It would be Greek tragedian in the sense that eventual downfall would have sprung from either The Future’s payback for its Enlightenment protagonist’s naive and hubristic idea of never-ending Progress or it might simply have been written in the stars of mankind’s Icaris-like inventiveness. But I am perhaps beginning to sound like I have been smoking something.....so I’ll park the daydream now.

Being of mature years, never occupying a strata beyond the ordinary, but having lived and seen a thing or two, I find your daydream realistic in concept and hopeful in outcome. For everything there is the pro and con, and being human-natured we make frequent use of both in our time here on the temporal plane. Conservatism is the innate understanding that utopia is an illusion that never materializes into heaven on earth. Hell is its inevitable outcome, yet conservatism needs the counterbalance of liberalism, and vise versa. Finding the balance is the hard part.

‘The dominant market is for commentary (and venting) on the current here-and-now of Progressivism’s social and political folly. ‘

You got me Graham!

Great essay. It’s a cliché, but I learned more about politics, the siren seductive pull of authoritarianism, the nature of language, and the power of propaganda from one Orwell novel than from all the non fiction commentary I have ever read on those topics.

And the stand up comedy of Bill Hicks taught me to be cynical and sceptical about all of it.

ATB